Scan to scam: how thieves can steal credits at cashless music festivals

A curious case of 'quishing' (QR code phishing) at certain cashless music festivals

Convenience is king, especially at music festivals where every extra minute spent in line can prolong the queue with hours. As a music enthousiast, I understand why crowds and crews choose cashless payments over any alternatives, but they may not realize that this comes at the cost: under the right conditions, it turns out to be incredibly easy to collect others’ remaining credits while also locking them out of their account, or even collecting their enterance wristband.

Cashless payments aren’t exactly new to music festivals here in Belgium, with “Tomorrowland” using Pearls as their virtual currency for years now. Most of these cashless systems work with RFID (radio frequency identification, such as NFC) technologies embedded into the festival entrance bracelet, which allows users to top up their balance at several cashless points positioned throughout the festival grounds. After the festival, this virtual currency can be refunded.

While RFID is not perfect, it is typically not possible to clone a wristband of a festivalgoer because the data can be encrypted to only allow interactions between authorized tags and devices. This is also what “Rock Werchter” wrote on their website when they announced that this years’ editions were going to be completely cashless:

Even if a thief would break past this encryption layer, it would be incredibly hard to steal enough credits to be worth their time, as they would have to hold a cloner device right next to their victims’ wristband for multiple seconds. It simply would not be practical.

Enter QR codes. New this year is that festival wristbands can be equipped with a QR code on the RFID tag, allowing ticket holders to easily top up their balance by scanning it with their mobile phone:

The back of the wristband features a unique identifier consisting of 6 uppercase letters. This side of the chip is typically not visible to by onlookers, as it is facing the wrist of the wearer.

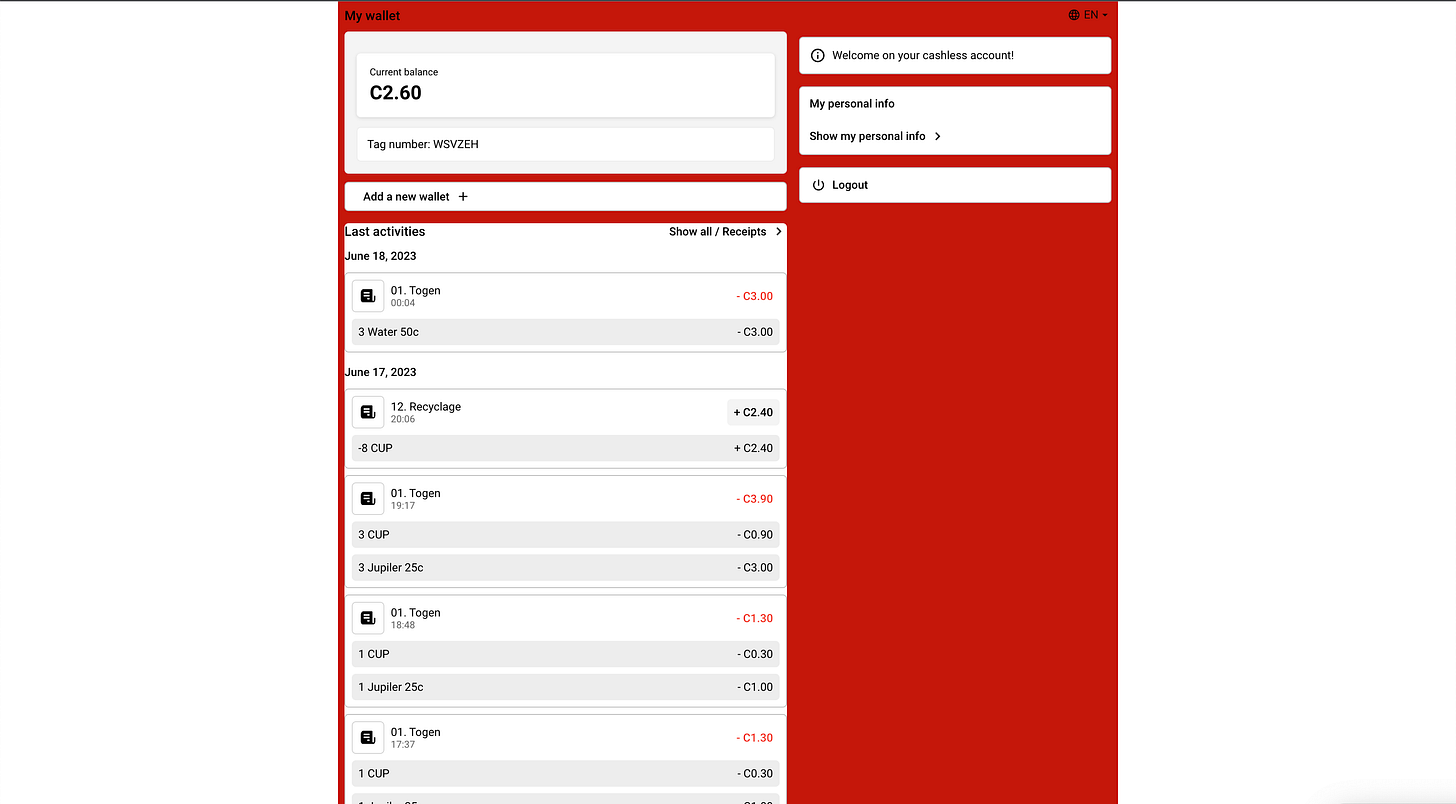

This ID key is used to link your wristband to your online accounts which you can use to request a refund once the festival is over:

With almost 309 million possible combinations, it is unlikely for someone with malicious intentions to guess the code manually. Assuming that automated guessing attempts would be blocked, hiding the tag number at the back of the wristband seems like a good solution, if it weren’t for the fact that the code is hiding in plain sight: the QR code!

Let’s take a look at the decoded data contained within the QR code:

As it turns out, these QR codes contain a link to weez.li, which has the short_tag XMLFBM in as a URL parameter. If we can simply read the QR codes of other festivalgoers, we can obtain their tag number and claim their refunds.

I did a little experiment during last weekends’ TW Classic Festival: how easy would it be to collect as many valid QR codes as possible, without looking suspicious? As comes in handy during rock concerts, it is common practice to raise ‘devil horns (🤘)’ in between songs to show appreciation for the band, resulting in a sea of QR codes emerging from the crowd:

Social media also proved to be a useful resource, as people would post pictures of their wristbands online, along with the hashtag of the festival

Even if the QR code is blurred or not completely visible, it may still be possible to retrieve the data because most of the QR code data simply contains error correction bits. Here’s a link to a great article that explains the technical bits on how unreadable or damaged QR codes can be restored:

Using stable diffusion AI forensics, QR code reading apps will likely improve to read QR codes from afar and with limited visibility, which would make it easier for non-technical attackers to steal a considerable amount of bracelet tags in a short amount of time.

Attack scenario #1: Claiming leftover terminal or cash top-ups for unlinked accounts after the event

In some scenarios, it seems possible for an attacker to refund any leftover currency to their account rather than their victims’ account, simply by providing their IBAN to their newly linked tag:

Note that, according to the documentation, festivals may also automatically refund the remaining funds to the payment provider that the top-up was made online with (e.g. Payconiq), in which case the attacker would not be able to reroute the funds to their account. For on-site top-ups, such as through terminals or cash, the remaining funds can be claimed by anyone as long at the bracelet owner did not register an account.

Attack scenario #2: Wristband swapping by reporting scanned bracelet as ‘lost’

According to the cashless FAQ section, it is possible to deactivate an old wristband by reporting it as lost, as long as you’ve registered it. Since this technique allows users to claim unclaimed wristbands, an attacker could register the tag of another festivalgoer that has topped up their unregistered bracelet, and then go swap it at the helpdesk, where, according to the documentation, they would deactivate the wristband of the user and load their credits onto your account:

Even if they would ask for our ticket, as a double confirmation, a procedure that is not listed on the website, we could show the ticket number or QR code that could be disclosed on the portal:

When succesful, this attack would allow thieves to steal and recover the funds of another festivalgoer by scanning their wristband and going to the helpdesk. Note that we have not tried this full flow at the festival itself, but given that you already have their valid ticket number and their wristband linked, we believe that this attack is likely to be succesful according to the FAQ.

Attack scenario #3: revealing what, when and where they ordered

There’s also a less intrusive scenario that allows an attacker to link the bracelet, log into the portal and monitor the live transactions of the festivalgoer:

Interestingly, if you look at the raw data that is loaded into the page, it also contains the exact locations of where these transactions happened, meaning that you can track where people are or what concerts they are attending simply by monitoring their transactions:

Note that the identity of the user is not revealed.

What’s the risk?

While the refund attack technically work, the likelihood of it being exploited on a large scale is rather low. While anyone can easily create multiple anonymous accounts without e-mail confirmation, they would still need to supply valid IBAN numbers to claim the refunds, which leaves a paper trail that may identify them. Assuming most people do not have hundreds of euros left on their accounts, the risk vs possible reward may not be interesting enough for people to start collecting QR codes. Once the gains are too big, they may get noticed by either their victims trying to get their refunds back, or any fraud detection algorithms these payment services typically implement.

The wristband swapping scenario might be the more dangerous one, because, when succesful, it would leave no traces: the attacker can simply create an account with dummy data, link it to the bracelet, go to the helpdesk to disable to original bracelet and get a new one, and cash out. It would however still require them to go try their luck at the helpdesk, with the registered bracelet and if available/needed the stolen ticket ID, which does pose a risk to get caught.

We believe that the real-time tracking scenario would be less risky to execute as anyone could simply create a fake account and link it to an unclaimed QR code around the wrist of a person of interest without leaving a lot of traces. Luckily, the amount of revealed information is limited to the individual orders, at what time and where. Nevertheless, we do believe that this is a valid privacy concern that the audience needs to be informed about.

How can I avoid someone links my festival tag?

Do not share pictures featuring your QR code online

Register your account upfront: a tag can only be linked to one account, so if you link your wristband prior to the festival, nobody will be able to link your tag before you do.

Put a piece of non-translucent tape over the QR code during the festival.

Wear one of these old-school sweatbands over your tag:

How can this system be fixed to prevent this?

There’s a couple of solutions to prevent this type of quishing (QR-code phishing) from happening.

Event organisers could require everybody to sign up prior to topping up their cashless wristband, but this introduces friction and forces people to hand over their personal details, which could raise privacy issues. I haven’t been able to find any unclaimed wristbands for Graspop Metal Meeting, leading me to believe that registration at the latest on check-in.

Upon linking the bracelet, event organisers could also ask to confirm the name listed on the ticket as an extra layer of protection, but this also has edgecases with separate top-up cards that can be shared by a group of people. This will also require them to share the names with the cashless vendors upfront.

In an ideal world, the QR code only works for top-ups. To view transaction data and request refunds, a separate code on the back of the chip could be used.

Closing notes

The introduction of cashless payments at music festivals is a much welcomed innovation, but as with all things we should ask ourselves the question '“how will someone abuse this?”. At mass gatherings with hundreds of thousands of annual visitors, you can be assured that someone will try to push the boundaries. Music festivals already heavily invest in physical security, and as they continue to pivot into the digital world, implementing and enforcing cybersecurity standards on their vendors and suppliers will be an absolute necessity.

Note from the author: the affected vendor and festivals have had a chance to read this and suggest corrections prior to it being published.